Thanks to countless books, television shows and movies, the Wild West has often been romanticized, the wide open prairies, drinking whisky in quaint saloons, the savage Red Indians and gunfights galore.

The truth, as the truth often is, is somewhat more complicated than what the Hollywood lens has shown us about this pivotal part of American history. In reality, we really know very little about this tumultuous time in history.

So, it is through the lens of the camera we take a look as some rare pictures of the people and places from a time that was dangerous, brutal and some times wholly unforgiving.

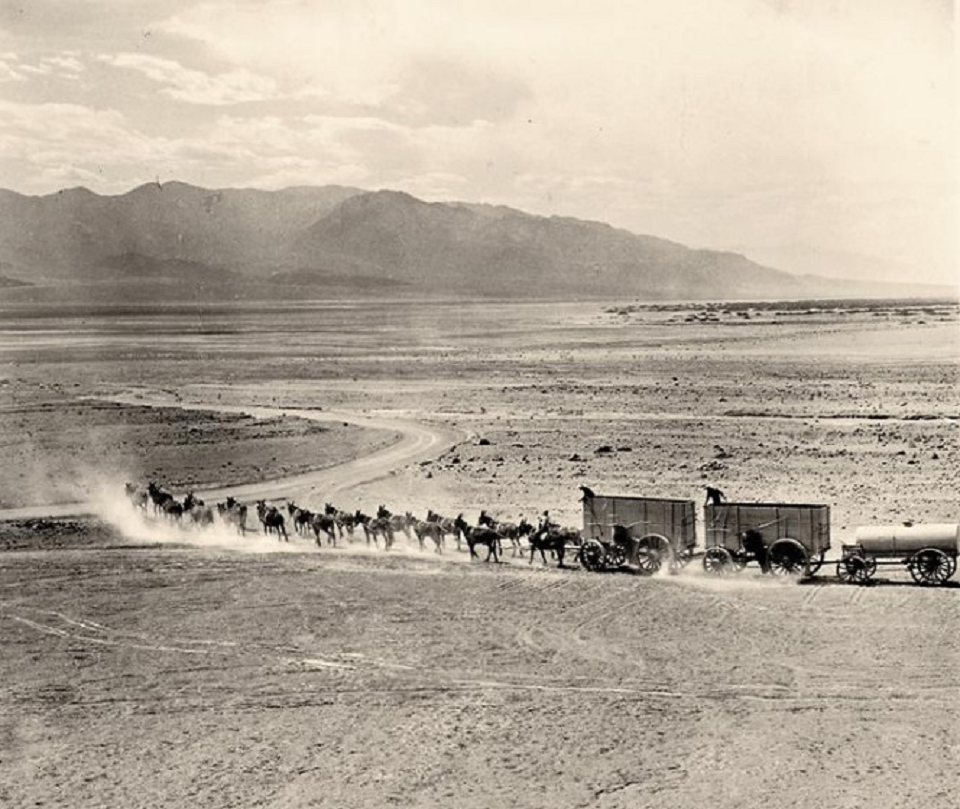

Transporting Borax Through Death Valley

This photograph was taken sometime between 1883 and 1889 showing a 20-mule team transporting borax ore out of Death Valley. These solid oak wagons were among the largest ever pulled by draft animals, designed to carry 10 short tons (9 metric tons) of borax ore at a time.

The first wagon was the trailer, the second was “the tender” or the “back action”, and the tank wagon brought up the rear. Due to their rugged construction, no wagon ever broke down in transit on the desert.

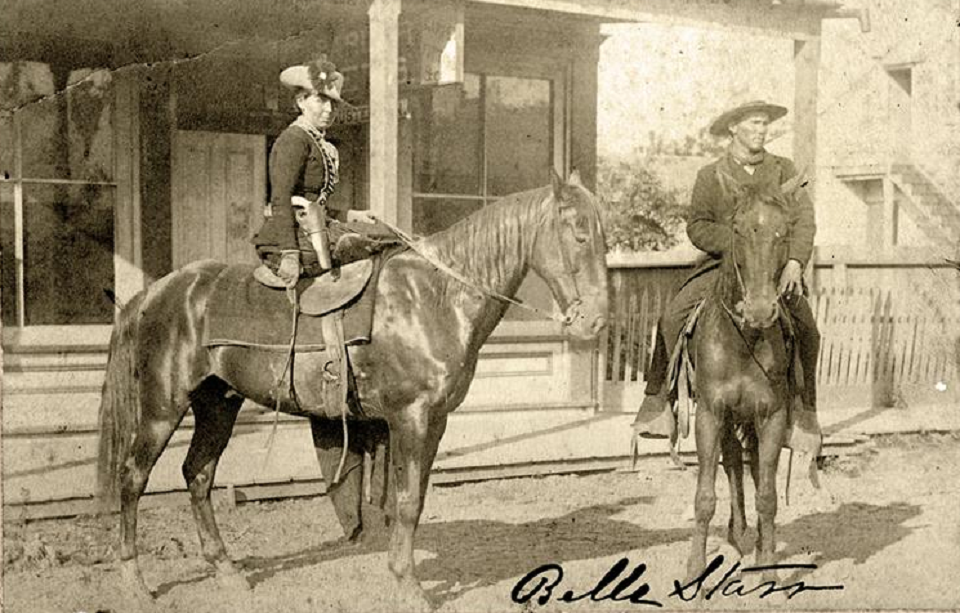

The Outlaw Queen

Most would assume the role of the outlaw was strictly a male dominated occupation. However, this couldn’t be further from the truth as this photograph clearly shows.

This is the notorious outlaw Myra Maybelle Shirley Reed Starr, better known as Belle Starr. She was associated with the James–Younger Gang, a group suspected of having robbed banks, trains, and stagecoaches in at least eleven states.

In 1883, Belle and her husband Sam were arrested by famed lawman Bass Reeves, charged with horse theft and tried before “The Hanging Judge” Isaac Parker in Fort Smith, Arkansas. Serving nine months at the Detroit House of Corrections in Detroit, Michigan.

On February 3, 1889, two days before her 41st birthday, she was fatally shot and killed. It’s a murder case than remains unsolved to this day.

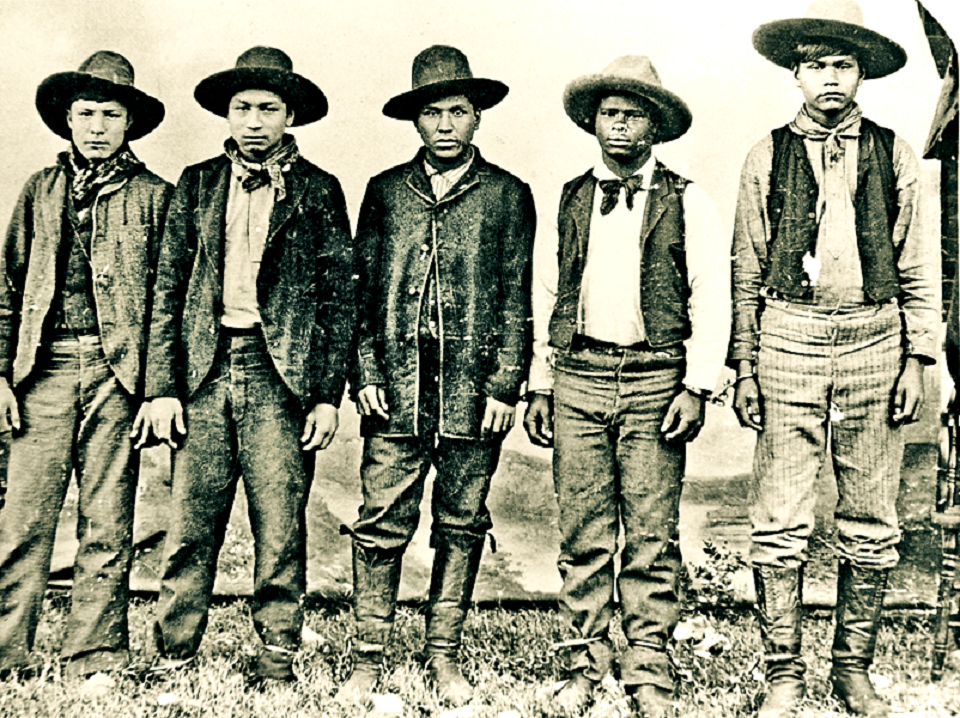

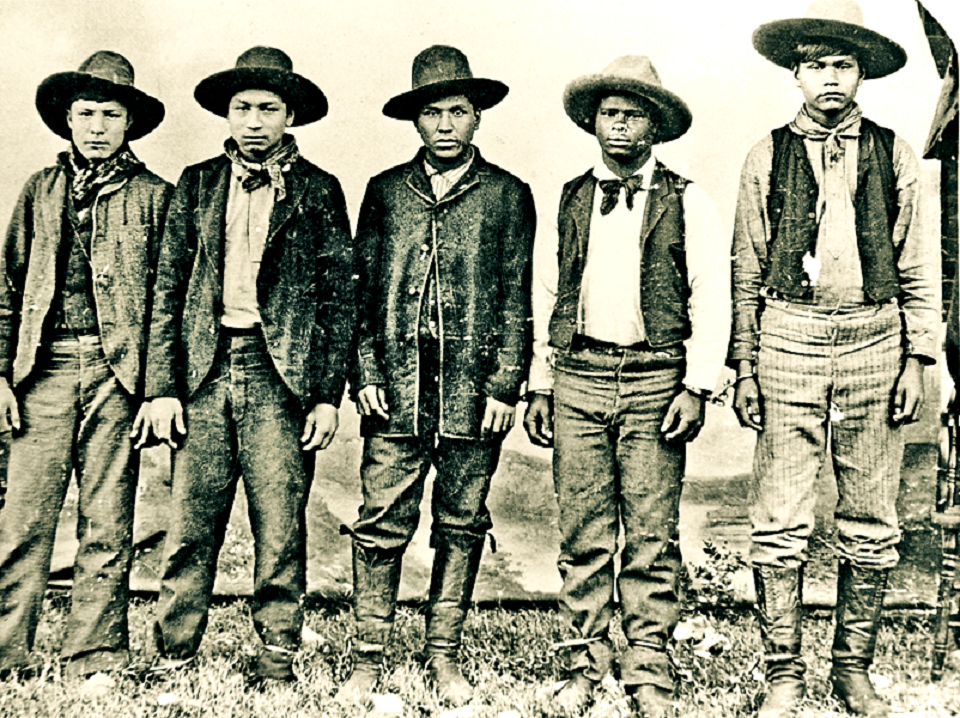

The Rufus Buck Gang

Much like with our previous entry, most assume when picturing a band of outlaws, a group of rough and tough white men, but that wasn’t always the case as this photograph of a multi-racial gang shows.

Formed by Rufus Buck, pictured in the center, its members consisted of part African Americans and part Creek Indians. They operated in the Indian Territory of the Arkansas-Oklahoma area from 1895 to 1896, holding up various stores and ranches in the Fort Smith.

Over the span of just a few months, they killed U.S. deputy marshal John Garrett on July 30, 1895, murdered and raped several women before being captured and sentenced to death. They were hanged on July 1, 1896 at 1 pm at Fort Smith.

Comanche Chief Quanah Parker

Quanah was the son of the famous white captive Cynthia Ann Parker, who, at aged just 10 years old, was kidnapped by a Comanche war band which had attacked her family’s settlement.

Parker was adopted by the Comanche and lived with them for 24 years, completely forgetting her white ways. She married a Comanche chieftain, Peta Nocona, and had three children with him, one of which was Quanah Parker.

In 1871, after the capture of several prominent Kiowa chiefs, Quanah would emerge as a dominant figure in the Red River War, where the United States Army tried to forcibly relocate the tribes to reservations in Indian Territory.

The Texas Rangers

The rangers were founded in 1823 when Stephen F. Austin, known as the Father of Texas, employed ten men to act as rangers to protect 600 to 700 newly settled families who arrived in Mexican Texas following the Mexican War of Independence.

From its earliest days, the Rangers were surrounded with the mystique of the Old West. Although popular culture’s image of the Rangers is typically one of rough living, tough talk and a quick draw it’s more likely their legendary aura was in part a result of the work of sensationalist writers and the contemporary press, who glorified and embellished their deeds.

While some Rangers could be considered criminals wearing badges by a modern observer, many documented tales of bravery and selflessness are also intertwined in the group’s illustrious history.

Olive Oatman

This 1863 photograph shows a stoic looking Olive Oatman sporting a rather interesting facial tattoo. In 1851, Oatman’s family and a company of Mormon Brewsterites were attacked and killed while traveling from Illinois to California.

The attackers, believed to be Apache at the time but most likely Tolkepayas according to modern historians, clubbed the group to death but spared Olive and her younger sister Mary Ann and enslaved them for one year. The girls would then be traded to the Mohave people, where Olive would spend the next four years of her life. Sadly her sister died from starvation during this time.

When a Yuma Indian messenger called Francisco arrived at the village with a message from the authorities at Fort Yuma, her presence there was discovered. After several requests and threats of violence from the commander at the Fort, Oatman would return to her own people.

A surprise was waiting for her upon her arrival. Believing her entire family had been wiped out in the massacre, Oatman was astounded to discover that her brother Lorenzo was alive and had been looking for her and her sister. Their meeting made headline news across the West.

She became somewhat of an oddity in 1860’s American society due to the prominent blue tattooing of her face, a reminder of her time with the Mohave people, making her the first known white woman with Native tattoo on record.

The Long Walk

This photograph was taken in 1873 and shows a group of Navajo people near Fort Defiance, New Mexico after being dispossessed of their homeland during the treacherous “Long Walk.”

The Long Walk of the Navajo, also called the Long Walk to Bosque Redondo, refers to the 1864 deportation and attempted ethnic cleansing of the Navajo people by the United States federal government.

The Navajo themselves refer to this event as “The Fearing Time” due to the fact that during this they failed to provide an adequate supply of water, wood, provisions, and livestock for the 300 miles (480 km) perilous trek to Fort Sumner.

Many of the around 9000 Navajo forced to make this journey beginning in the spring of 1864, many of them women and children, starved, died from disease or froze to death during the winter because they could make only poor shelters from the few materials and resources they were given.

In 1868, the Treaty of Bosque Redondo was negotiated between Navajo leaders and the federal government allowing the surviving Navajo to return to a reservation on a portion of their former homeland.

The Cowboy Detective

This is a photograph of the famous cowboy detective Charles Siringo (right) and his colleague W.B. Sayers, although that is unlikely to be his name as Siringo in his book, A Cowboy Detective, changed the names of his cohorts in order to protect their identities.

After witnessing the Chicago Haymarket affair, the bombing of a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, Siringo joined the Pinkerton Detective Agency, using famed lawman Pat Garrett as a reference. Siringo was an early undercover operative, infiltrating gangs of robbers and rustlers, making more than 100 arrests.

Siringo would write several books detailing his time as a detective, but his most famous would be about his time as an agent for the Pinkerton National Detective Agency during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the aforementioned A Cowboy Detective.

Big Foot

Spotted Elk, or Big Foot, was a Lakota Sioux chief highly renowned for his skills in war and negotiations. The son of Miniconjou chief Lone Horn, he became the chief upon his father’s death. On December 29, 1890, he would famously take part in the Battle of Wounded Knee, better known today as the Wounded Knee Massacre.

The massacre would take place when a detachment of the U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment led by Colonel James W. Forsyth decided to try and disarm a band of Miniconjou Lakota. One version of events claims that during the process of disarming the Lakota, a deaf tribesman named Black Coyote was reluctant to give up his rifle, claiming he had paid a lot for it.

When his rifle went off, supposedly by accident, the soldiers opened fire. As the photograph above attests to, Spotted Elk would become one of the many casualties. Once the smoke had lifted, 152 Lakota Sioux lay dead, including women and children.